The new Union Workhouse in Abingdon, known locally as ‘The Grubber’, was the first in England to be constructed following the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act. The majority of the parishes covered by the union were in north Berkshire, as was Abingdon at this time, but several neighbouring Oxfordshire parishes were also included. Regulation was in the hands of a Board of Guardians representing each parish. The first Governor of the Abingdon Union Workhouse was Mr Richard Ellis who survived an attempt on his life.

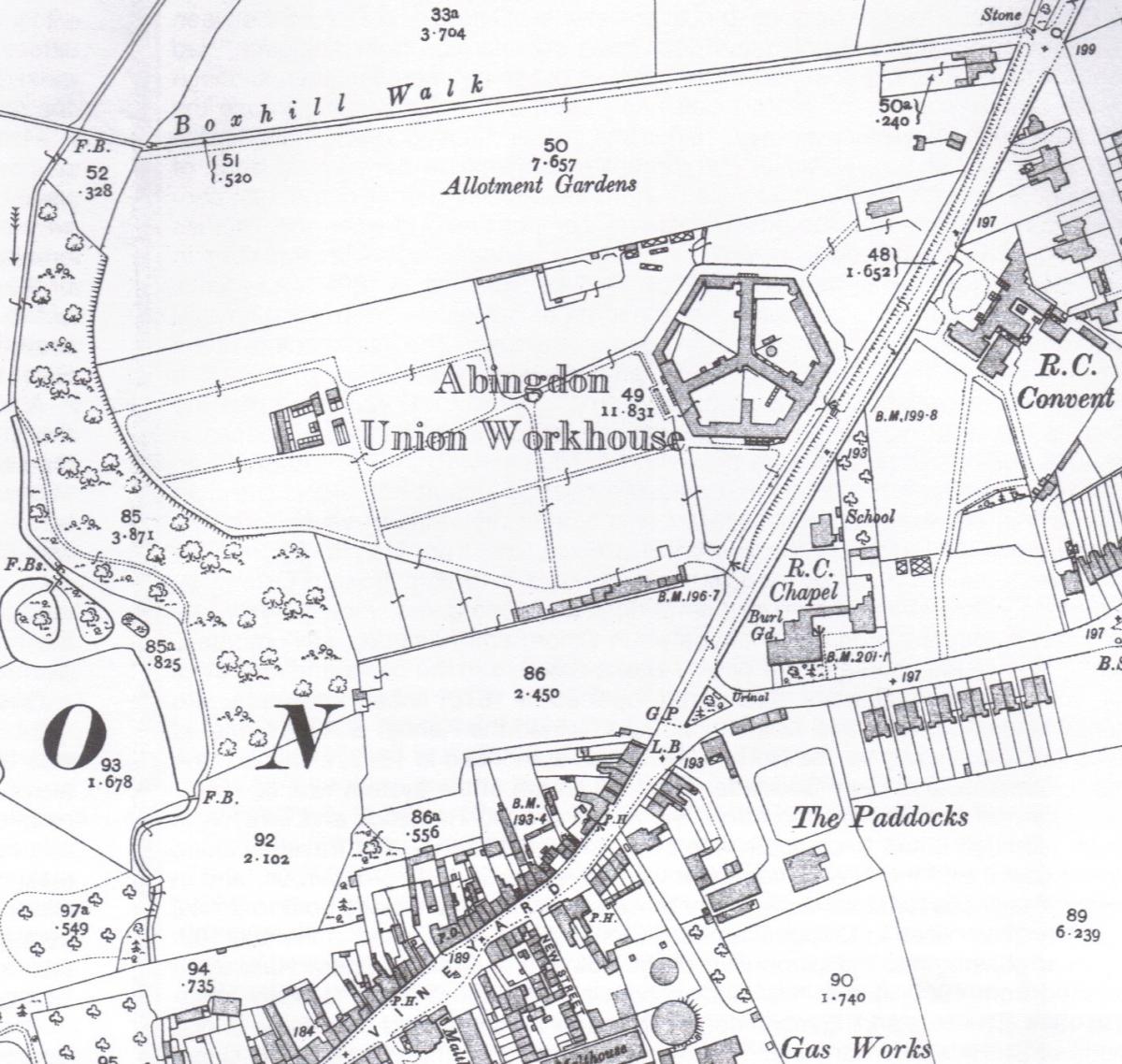

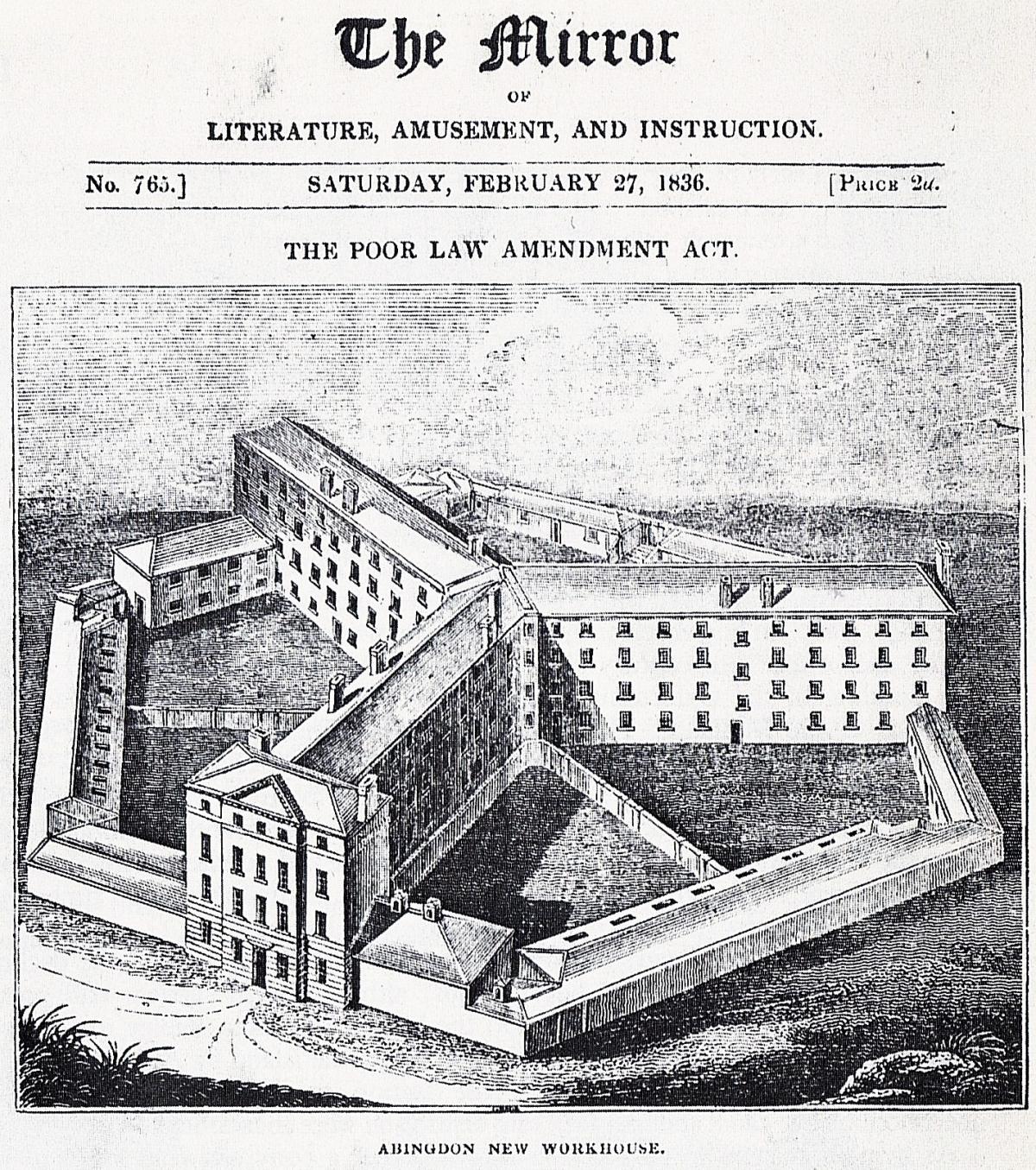

The chosen 12 acre site at Boxhill then lay on the edge of town – Northcourt was still a distant hamlet. The building, designed by Samuel Kempthorne, was a variation on his model ‘Y’ plan. The buildings forming the ‘Y’ were enclosed by an outer hexagonal arrangement of walls and low-rise buildings. This enabled the provision of segregated outdoor yards for men, boys, women and girls. The Governor’s quarters were centrally situated for easy supervision of these different areas. The design was published in “The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction” in February 1836.

Victorian images portray workhouses as cold and cheerless with an unrelenting diet of gruel. There was certainly a distinct lack of variety in the diet. Tables published in the “Berkshire Chronicle” in March 1836 quoted the normal daily recommended diet: breakfast, bread and gruel; dinner, cooked meat or soup, bread and cheese; supper, bread and cheese. No obesity problem there!

The dayrooms, dining hall and chapel were heated by hot water pipes, and the building was lit by gas from the new gasometer turned on in September 1834. Collecting and storing rainwater for use throughout the building might be considered today a green credential.

Quarterly advertisements in the local press invited the town’s traders to tender for supplying the essentials: flour for bread, meat particularly bacon and mutton, cheese, and oatmeal. An advertisement by the Board of Guardians in 1871 requested tenders for beef ”consisting of brisket, thick flank, veiny pieces and clods without bone” – clods were one of the cheapest cuts, fatty muscle from the shoulder.

Contrast this with the supper provided in November of the same year by the Mayor, Walter Ballard, for his invited guests in the Council Chamber: roast beef, ‘gelantines’ of veal, tongues , hams, roast and boiled fowls ? la béchamel and compotes of pigeons, a selection of eleven desserts washed down by sparkling champagne, port, sherry and claret!

At Christmas some effort was made to make the day more special with Christmas dinner and small gifts of tobacco, snuff or sweets. Frequently the Governor and his friends would provide musical entertainments and readings, presumably from uplifting literature, for the inmates. In 1929 a 14-year old Abingdon schoolboy Ralph ‘Laurie’ Liddiard, later well-known to employees of the Pavlova Leather Company, was appointed as Master’s clerk. Laurie’s experience as clerk was featured in the Oxford Times in April 1982. He recalled roast turkey or beef at Christmas, a major departure from the usual fare. The last Christmas dinner was a lavish affair of roast beef, roast pork, boiled potatoes and green vegetables followed by Christmas pudding washed down with beer and mineral water.

The Local Government Act (1929) abolished the workhouse system. Some workhouses became geriatric hospitals but the Abingdon Union Institution was demolished in 1932. Part of the site was fenced off for recreational use but the remaining ten acres were ‘ripe for development’. In 1934 the Borough Council agreed in principle to the erection of houses not exceeding 10 per acre, and a year later plans were approved by the Highways Committee. The developers were Oxdon Lands Ltd, a building firm from Coventry. The roads on what became known as the ‘workhouse estate’ were named in honour of two 19th century men whose portraits hang in the Council Chamber: Sir Charles Abbot, born in Abingdon and one-time Speaker of the House of Commons and Sir Frederic Thesiger, MP for Abingdon from 1844 to 1852.

Today the only surviving trace of the workhouse is a section of the perimeter brick wall visible across Boxhill Recreation Ground.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here