ABINGDON Market Place in the late 19th century was dominated by imposing buildings, solidly built and all looking as though they would last forever: the London and County Bank (now NatWest); the Corn Exchange and the Queen’s Hotel. They gave the Market Place a certain grandeur.

Today only the bank remains, and the Corn Exchange is one of Abingdon’s ‘sadly missed’ buildings.

Abingdon lay in a rich barley-growing area which provided the raw materials for its malting and brewing industries.

Farmers and dealers had been clamouring for premises where the Monday corn market could be accommodated and general agricultural business discussed.

In 1849, a meeting of ‘Agriculturalists, Dealers and Inhabitants of Abingdon’ passed a resolution requesting the Corporation to infill the arcade of the County Hall with glass so that it could be used as a Corn Exchange.

The new Queen’s Hotel, opened in 1864, offered limited facilities in the form of a commercial room and coffee room, but by 1879 the Corporation’s Corn Exchange Committee was insisting that a custom-built exchange was ‘of the first importance’.

However, it was not until 1884 that the Corporation finally bought the Oxford Arms and the Plough and Anchor Inn facing the Market Place as a site for the Corn Exchange.

The redevelopment of this site had the added advantage of improving access to the projected new cattle market between Bury Street and the rear of the High Street (now a service area and car park).

The competition to design the Corn Exchange was won by Charles Bell, an architect better known for designing Wesleyan Methodist chapels.

His winning entry called 'Bona Fide' envisaged a building 48 feet wide by 85 feet long consisting mainly of a large hall with a gallery at one end.

Bell also, coincidentally, designed the adjacent London and County Bank and the Abingdon Cottage Hospital, formerly in Bath Street.

The foundation stone was laid by the Earl of Abingdon, the town’s High Steward, on August 11, 1885, and construction completed within a year.

The building was of brick with stone dressings in an Italianate style. There was a double-arched entrance, and the statue of Ceres which dominated the pedimented façade was donated by the town’s MP and member of the council, John Creemer Clarke, who had been a staunch supporter of the project.

The official opening of the Corn Exchange on April 29, 1886, was performed by the mayor, Mr Alderman Morland, who declared that the chief aim of the council was 'to bring trade to the old town of Abingdon' and to this end the scale of charges was lower than in other places. In addition the first year’s rental of 31s 6d covered a period of 16 months.

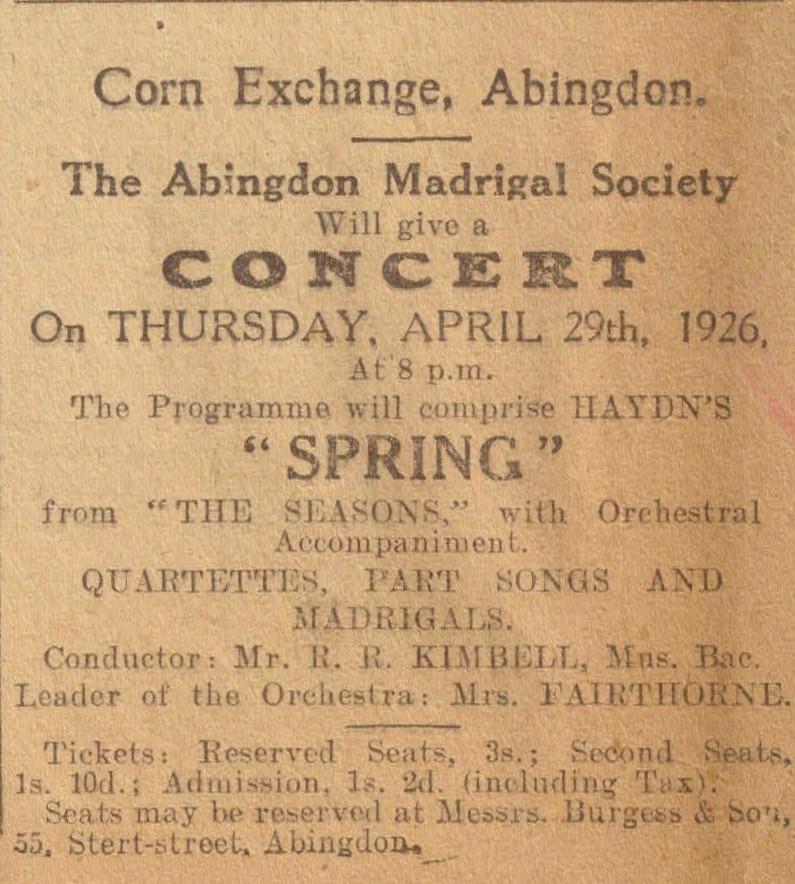

Invited guests attended an evening concert in the exchange. The following evening the musical association also organized a popular concert with back row seats priced at 6d.

In 1887 a licence was granted for the performance of stage plays. Plans were prepared in 1891 to enlarge the stage and re-arrange the dressing rooms to form cloakrooms at the entrance and improve access to the gallery by providing two staircases.

The Corn Exchange became a focal point in the business and social life of the town. It could seat more than 600 people as a venue for entertainments, concerts, plays and the new moving pictures.

Early public experience of moving pictures in Abingdon had been confined to Taylor’s cinematograph at the Michaelmas Fair in the early 1900s.

Now applications could be made to the borough council for licences to show films. The first showing in 1919 paved the way for competition in the 1920s with the newly-opened cinema in Stert Street.

During the Second World War a large ‘barometer’ was fixed to the façade allowing patriotic Abingdonians to salute the town’s efforts to raise funds to buy a Spitfire in the battle against ‘the Hun’.

It was also the venue for wartime dances and other social activities to raise morale. In 1948 Abingdon was adopted by Thames, New Zealand, under the Food for Britain Campaign; the Corn Exchange became the distribution centre for the food parcels sent by the residents of Thames.

In recognition the mayor and burgesses were granted Freedom of the Borough in October 1966. The street name Coromandel in south Abingdon recalls this link.

Post-war planners, like their Victorian counterparts, had no emotional ties to buildings which now stood in the way of progress, in this instance a traffic-free pedestrianised shopping precinct.

A new modern community hall, the Abbey Hall, replaced the Corn Exchange in 1966. It is much admired by students of modern architecture but will it be remembered with the same affection?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here