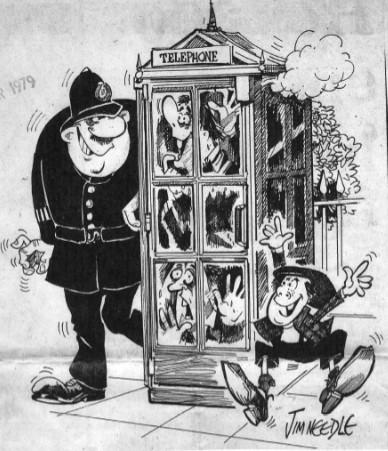

VANDALS who attacked kiosks in the early days of the telephone service in Oxford could find themselves in a spot of bother.

Anyone stealing the equipment ran the risk of being locked in for hours.

University students had discovered that the handset in the phone box could be used to make wireless sets.

They could then listen to their favourite radio programmes in comfort in their college rooms.

But wily telephone chiefs came up with a fiendish plot to beat the wreckers.

They fitted a device to the handset which, when triggered, would lock the kiosk door, trapping the vandal inside and setting off an alarm in the telephone exchange.

The door would remain locked until Post Office staff arrived to release their captive.

In 1979, Oxford Mail diary columnist Anthony Wood interviewed Bert Wood, of Banbury, who, as a young trainee engineer, recalled his first ‘catch’ – two undergraduates.

“As we approached, all I could see were the windows of the box totally steamed up, except for a small patch wiped in one of the panes out of which was peering a head.

“I let them out of the box and asked them if they had touched the equipment. They were very abusive – the phone boxes are much smaller than they are now. They must have been in there for nearly an hour.”

None of the vandals appeared in court because it was difficult to prove that those caught in the kiosks had committed the damage.

The trap remained in place for about a year, but was then abandoned after discussions between the Post Office, police and the university.

Although the trap caught many young people at first, sympathetic taxi drivers learned how to release them before Post Office engineers arrived.

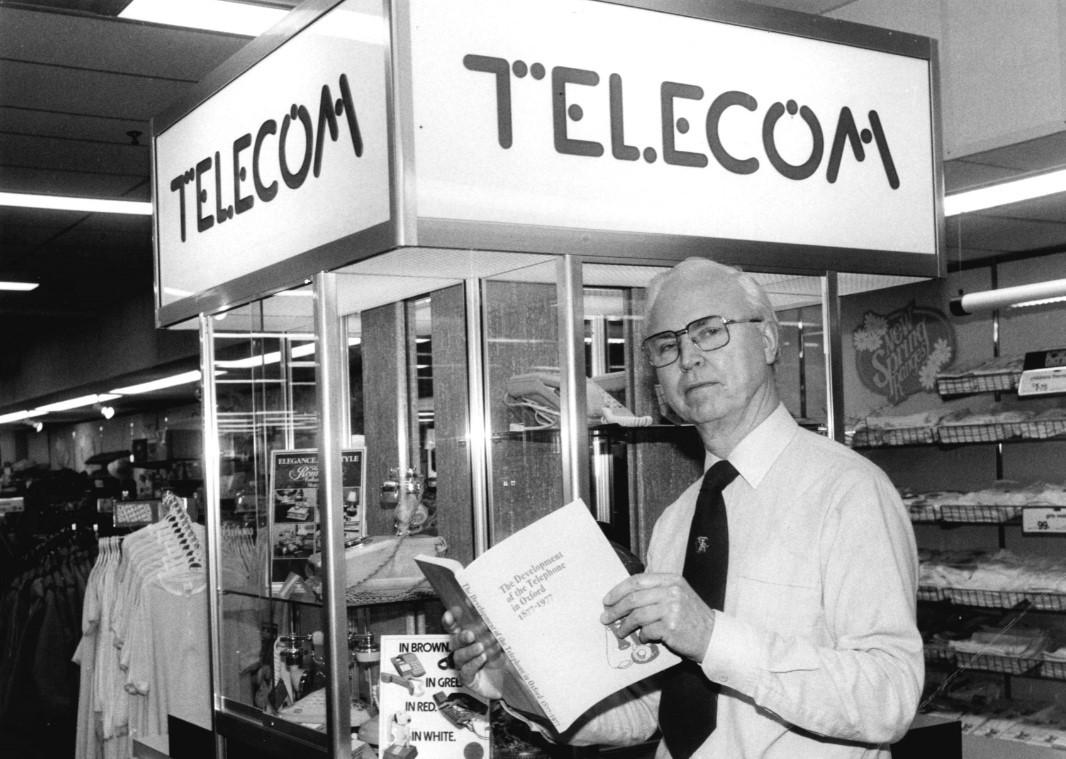

The story is told in a book on the 100-year history of the telephone in Oxford, written by Reg Earl, curator of Oxford’s telephone museum.

As we recalled (Memory Lane, March 16), he set up the museum with kiosks, switchboards and telephones of every shape and size in a small room below the Oxford exchange in Speedwell Street.

The book reveals how difficult it was to persuade people to install phones in their homes in the early days.

In 1877, the fire brigade and Post Office held the only phones in Oxford and it was not until 1886 that the first exchange opened in the city. It had just 55 subscribers by 1889.

Many people were put off having a phone as the cost of calls was high – early subscribers had to pay ninepence for a call to London at a time when the average wage was less than eight shillings a week.

To encourage more people, the Edison telephone company offered free calls for a year to new subscribers.

However, the firm imposed a draconian rule stopping those already connected from allowing friends and neighbours to make calls on their phones.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel